Ideonomy: A Science of Ideas

November 23, 2024Ideonomy is the "science of ideas" as formulated by Patrick Gunkel.

Ideonomy is a fascinating discipline, but it can be daunting to approach at first. The ideonomy homepage (last updated in 2006) is filled with disorganized typewritten documents and inscrutable charts, and the casual reader could be forgiven for thinking that ideonomy is trivial or nonsensical. Unfortunately, though Gunkel was a brilliant and creative thinker, his communication style was not always easy to follow.

In the hopes of creating a more accessible introduction to ideonomy, I will make my own attempt to explain what ideonomy is, how it works, and what it can accomplish.

Table of Contents #

- Why a science of ideas?

- Don't other sciences already study ideas?

- What can ideonomy do?

- What's an example of ideonomy in practice?

- (Aside) What is an idea, anyway?

- How is ideonomy performed?

- Why is now a good time for ideonomy?

- What's next for ideonomy?

Why a science of ideas? #

The foundational insight of ideonomy is that ideas are part of the natural world. Just as humans are part of the natural world, the thoughts and ideas generated by human minds are also natural phenomena. Accordingly, we should expect there to be underlying laws or patterns in ideas, the same way we observe laws that govern other natural phenomena. While most phenomena in our universe are examined through a scientific lens, ideas are often treated as magic. Ideonomy aims to remedy this.

Ideonomy is distinct from other sciences in its treatment of ideas as first-class objects, extracted from the particular context in which they are generated. Ideonomy treats ideas as "primitives" which can be enumerated, manipulated, and potentially combined with other ideas in novel ways. Ideonomy often works at a higher level of abstraction than other sciences, looking for connections between ideas that might otherwise seem distinct.

Gunkel is not the first individual to attempt to create a science of ideas - he names Peter Mark Roget and Fritz Zwicky as predecessors, among others. Furthermore, he notes that his formulation of ideonomy is idiosyncratic to his interests, methods, and style. In further developing ideonomy, we should expect to pick and choose among these methods, altering and developing them as necessary to pursue his desired aim - the examination and illumination of ideas.

Don't other sciences already study ideas? #

Ideonomy is distinct from other natural sciences in its scope - it aims to treat all ideas, regardless of whether an idea would typically fall under the purview of physics, chemistry, biology, or some other science. By focusing on a higher abstraction level than other sciences, ideonomy can identify patterns, symmetries and connections between these fields that might be hidden to researchers focused on a more specific area. The short-term goal is to accelerate discoveries in these fields; the long-term goal is the gradual understanding of the laws of ideas themselves.

A good example of this "higher level" thinking is Gunkel's description of "trees" in education:

The proof that our educational system is a failure need only be a tree!

Trees (dendritic structures and processes) are recognized to handful of supremely key patterns in all of Nature, and have definite types, properties, and laws. But our students are taught that trees are plants. The infinitely more important and fundamental definition is not taught at all! Not even the teachers know of it!

Trees are the key to classification, decision-making, memory, information theory, government, computer programs [etc.] - but we tell generation after generation of schoolchildren that a tree is just a type of plant!

An educational system that does that is topsy-turvy.

Certainly it is NOT teaching 'basics'!

Gunkel's attitude towards education mirrors his attitude towards academia in general. He held a deep disdain for what he saw as needless over-specialization and compartmentalization in the sciences, and saw ideonomy as a tool to combat this trend.

Accordingly, an ideonomist might focus exclusively on trees, as manifested in all disciplines.

What can ideonomy do? #

Gunkel provides countless possible uses for ideonomy, but I believe these can be narrowed down to two categories:

- Generate (or discover) new ideas

The first and most obvious use of ideonomy is as a tool for generating ideas. If ideonomy is successful in identifying reliable ways to manipulate ideas, these methods could be applied to create novel and valuable ideas in a systematic fashion. This encompasses human-directed brainstorming as well as automated ideation by AI. If ideonomy is capable of furnishing even a moderately automated method of machine-driven ideation, it will be worth its figurative weight in gold.

- Help humans understand the universe

To Gunkel, investigation of the universe was one of humankind's greatest imperatives, and ideonomy represented his attempt to contribute to this species-spanning project. In particular, ideonomy aims to scientifically treat an aspect of reality that has not typically been investigated in a scientific or empirical manner. In this sense, simply understanding more about how ideas work would be its own reward.

What's an example of ideonomy in practice? #

It might be useful at this point to give an example of how ideonomy can work in practice. An illustrative example might be Gunkel's supposition of "proseases," aka "good diseases." Gunkel stumbled across this concept by taking an ideonomic "operator" - negation - and applying it to the phenomena of disease:

Clearly if the predicted good diseases (or proseases) do in fact exist, then they are apt to be of immense importance, and they may almost double the 'size' of future medicine... New and novel intestinal, oral, and skin microflora might be created to improve human health and the body's abilities and efficiencies.

Gunkel's description accurately predicts the present-day phenomena of communicable probiotic therapies such as Lumina. Although Gunkel was likely not the first person to consider this possibility, it provides a positive signal that manipulating ideas in such a way can yield fruitful results, especially when performed across many phenomena in many fields. It bears repeating - the end goal of ideonomy is not just to facilitate discoveries on a one-off basis but rather to systematize and automate these types of discoveries in as many areas as possible.

(Aside) What is an idea, anyway? #

Gunkel notes that ideonomy, perhaps ironically, does not provide a real definition for what an idea is. In practice, a precise definition of "idea" is not strictly necessary in order to discuss or manipulate ideas, any more than a precise definition of "number" is needed to perform arithmetic. However, this lack of straightforward definition does make communication about ideonomy more difficult, and is a gap that should be filled at some point.

How is ideonomy performed? #

Gunkel himself noted that his methods were not necessarily the most direct or effective means of studying ideas, and that they should be modified and replaced as necessary as ideonomy matures. However, it is still useful to understand his initial approach.

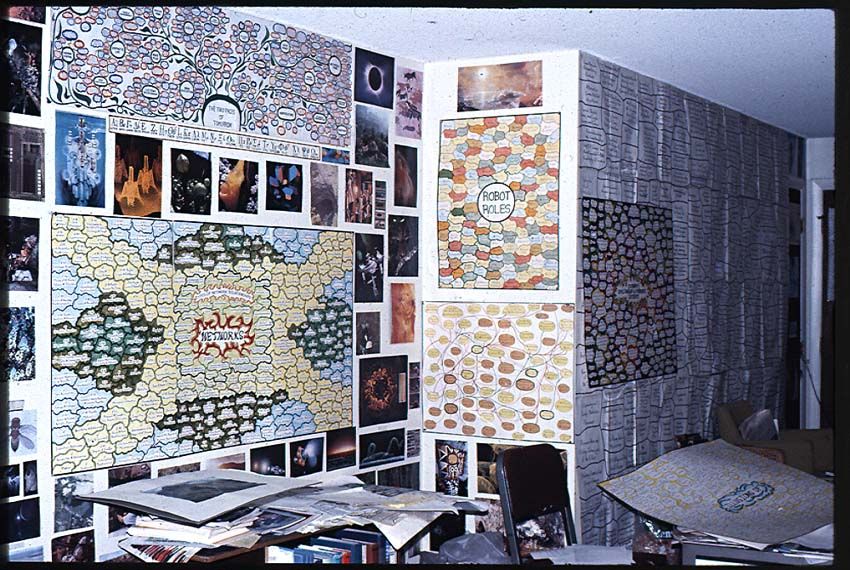

In Gunkel's methodology, the key enterprise of ideonomy was the creation of "organons", or tools for thought. An organon is any artifact that captures, describes, or otherwise treats an idea or a collection of ideas. The canonical example of an organon is a list.

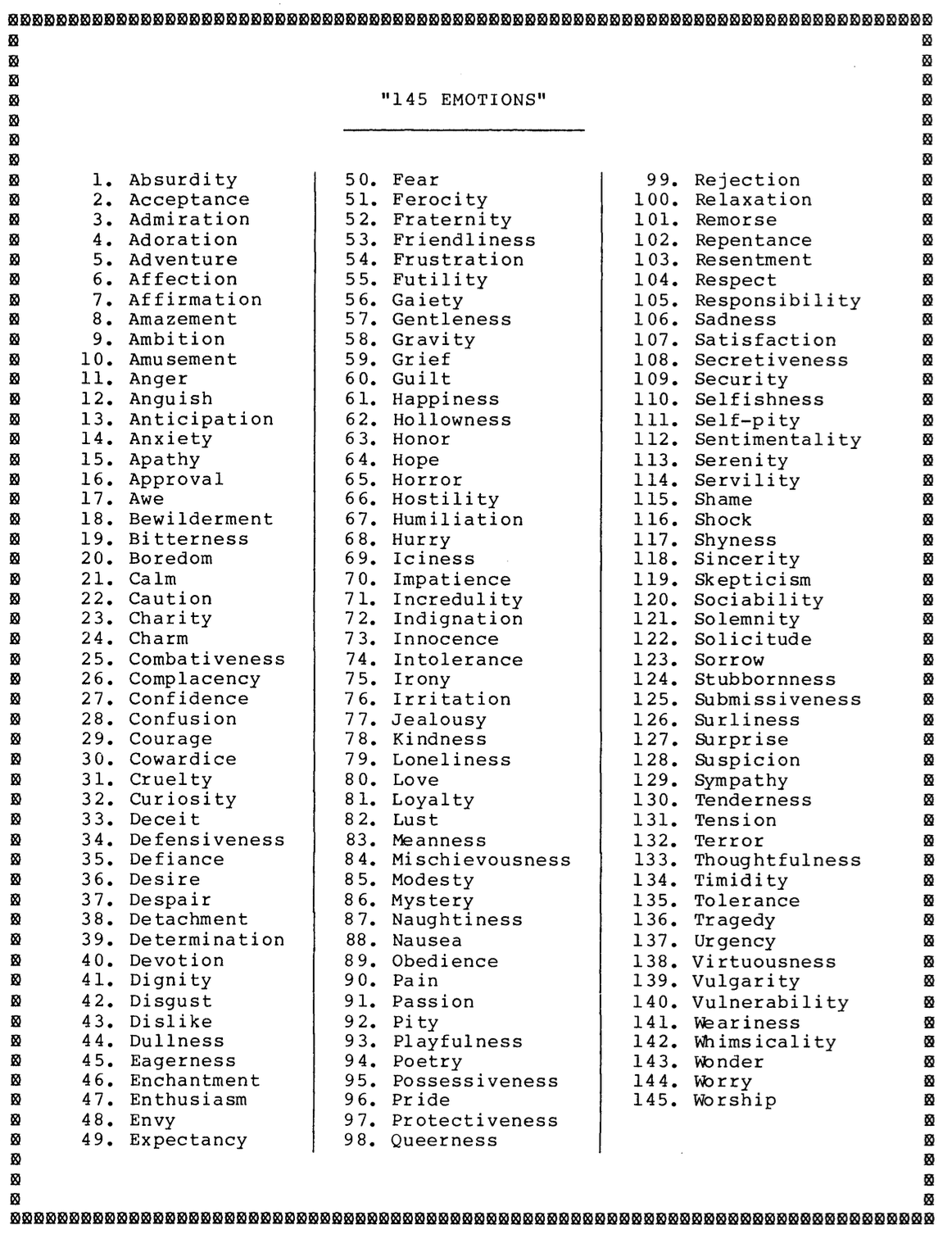

For example, a list of emotions:

These lists are typically unordered and non-exhaustive, and serve to provide illustrative examples of a particular phenomenon. An organon might also be a chart, graph, atlas, scale, dictionary, or some other artifact that captures an idea.

Once organons are created, they can be manipulated or combined to create new organons, and therefore new ideas. For example, the list of emotions might be combined with itself to create a list of complex emotions; "Absurd Worship" or "Worrying Acceptance". In this case, the generated "ideas" (emotion pairs) are quite simple, but the process can be applied to more complex organons in order to generate more complex outputs. Gunkel imagined that this process would initially be performed by humans, and would eventually be performed by computers.

Why is now a good time for ideonomy? #

Gunkel imagined that computers would eventually be an integral part of ideonomy, but the software (and hardware) of the 80's and 90's was not up to the task. Reevaluating in the present day, it's easy to imagine ways for computers to assist with, or perform ideonomic tasks. In particular, computer systems may:

-

Evaluate large idea spaces: Some of Gunkel's lists spanned tens of thousands of items. It's not reasonable to have a human evaluate each item, but it is potentially feasible for a computer to do so. Furthermore, language models can be used for "subjective" evaluation of ideas in a way that was previously limited to humans.

-

Draw from multiple areas of expertise: even the most brilliant human has an in-depth knowledge of a few fields at most. Conversely, an AI system with access to a large corpus of information may have knowledge across a wide array of domains, and may be able to draw connections between fields that are usually considered distinct.

In his writing, Gunkel described many "fanciful" ideas for ideonomic software- software for generating new words, navigating clusters of concepts, and more. Most of these ideas can now be built with AI tools, and may be built for research purposes or simply for fun.

What's next for ideonomy? #

In my opinion, there are a few open problems in ideonomy that need to be solved in order to "prove out" the field. In particular:

- How does one evaluate the quality, or "goodness", of an idea?

- In what contexts is ideation performed, and does the ideal strategy vary depending on the context?

- What is needed for AI systems to effectively mimic individual and collective human ideation?

These are not the only questions that need to be answered, but they are potentially the most pressing. My goal is to make progress on these questions, while spreading the word about ideonomy and encouraging others to explore it. I hope that this introduction has sparked your imagination, and that you are inspired to explore Gunkel's original works. And who knows, maybe you'll decide to become an ideonomist yourself!